One day a hunter called his friend to join him on a hunt so that he could see how his new dog performed. The two friends and the new dog ventured out to a lake where they knew lots of ducks were to be found. Before long, the hunter shot a duck which fell from the sky onto the water. The hunter sent his dog to fetch the kill. The dog leapt onto the lake, ran across the water, got the duck and ran back across the water. The hunter’s friend stared at the dog, stared at his friend, but said nothing. They continued to hunt and, indeed, shot another duck out of the air. Again the dog ran across the water, got the duck and ran back across the water. Again the friend stared but said nothing. The same thing happened a third time and finally the friend looked at the hunter and said, “Hey, don’t you notice anything strange about your new dog?” To which the hunter replied, “Yeah, now that you mention it, I can see that that dog can’t swim.”

_____________________________

Many jokes are wisdom stories in disguise. And many wisdom stories are simply jokes in finer clothing. I've known this story for far too long to be able to remember when I first learned it. And it has always amused me. Most of the time when i tell it, people get the humour and i get the laugh that I expect. There's usually a couple of listeners left scratching their head, but i figure they'll get it sooner or later. And, since i resist interpreting stories (as i've learned from Sufi storytelling), i leave it to people to be satisfied with the wit of the joke or to plumb the epistemological depths of this tricky tale.

I've never been a great joke-teller. I'm just okay though I'm a fine teller of tales. But the family gift of telling jokes lives strongly in my brother. He has a gift that i admire greatly. He is able to live a joke in a way that is captivating and never fails to infect his listeners not only with the humour of the joke but also with his own delight. And, over the years, i've developed a deep respect for jokes and joke telling. Both from experiencing and enjoying my brother's telling (and my father's joke telling from which we learned) as well as encountering the work of Cathcart and Klein in their series of books about philosophy, politics, and jokes. The first is a must-read: Plato and a Platypus Walk into a Bar...: understanding philosophy through jokes (Penguin, 2007). I'm also a fan of Existential Comics which is always funny, frequently hilarious (in a Monty Python-ish "Philosopher's Football Match" kinda way), and usually quite instructive about philosophical discourse.

I told this New Dog story in a class once where I had, as a guest, a seasoned academic. As i observed the expected laughter on the part of most of the students, I was surprised to see what I took to be a puzzled expression from my guest who i heard say, "I've never gotten that joke," which made me realize that it wasn't a puzzled expression but actually one of mild irritation, if not offence. I wasn't about to call attention to the comment but i did think, "Now THAT'S funny."

image source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/internetarchivebookimages/14597575387/

Saturday, February 23, 2019

Monday, February 18, 2019

Have Heart

One day a student of zen told her teacher that she was having a hard time

meditating. Worse still, having studied for several years, she was feeling like

she’s made no progress at all. “I am discouraged,” she said. “Can you tell me what

I should do to overcome this?” The zen master smiled and said, “encourage

others.”

_________________________________

This is a story I think about on a weekly basis. Which is, perhaps, a confession of how frequently i feel discouraged. But as with so many seemingly simple zen tales, there is an onion's worth of layers to this tale to be revealed. When i stop to notice the world around me, something i should always be doing more of, i see encouragement everywhere. And i feel this a necessary medicine in this dire times. I am reminded of Talmudic wisdom, "Every blade of grass has an angel that bends over it whispering, 'grow, grow.'" Such abundance.

Image source

_________________________________

This is a story I think about on a weekly basis. Which is, perhaps, a confession of how frequently i feel discouraged. But as with so many seemingly simple zen tales, there is an onion's worth of layers to this tale to be revealed. When i stop to notice the world around me, something i should always be doing more of, i see encouragement everywhere. And i feel this a necessary medicine in this dire times. I am reminded of Talmudic wisdom, "Every blade of grass has an angel that bends over it whispering, 'grow, grow.'" Such abundance.

Image source

Sunday, February 17, 2019

Being Prepared?

Two sages of Chelm went for a walk, one carrying an umbrella. Suddenly, it started to rain and the one without an umbrella said to the other, “quickly, open your umbrella.”

“It won’t do any good,” said the other.

“Of course it will do good. Is an umbrella not made to protect us from rain?"

“True. But my umbrella is old and full of holes."

“Goodness! Then why did you bring it along?"

“I didn’t think it would rain."

__________________________

I love stories of fools and tricksters and foolish-wise sages/animals/elders and so on. And nowhere is there to be found a population as rich in fools as the legendary city of Chelm. I read several Chelm stories to Taliesen last night and had us both laughing and, of course, cancelling out any relaxing bedtime story effect. I found myself laughing at some familiar tales all over again as i listened to myself read them and also listened through Taliesen’s experience. I was delighted and amazed at how quickly Taliesen picked up on the cleverness of the humour. I know many an adult who would not be so quick.

Once again i was impressed with the way that wisdom can be encoded in stories of comic misunderstanding. And this story, in particular, struck me as carrying in it something important to understand better about our current moment of climate crisis. But i’ll leave off carrying that thought any further here and let the story work in the way that stories work.

image: Vyacheslav Beda

“It won’t do any good,” said the other.

“Of course it will do good. Is an umbrella not made to protect us from rain?"

“True. But my umbrella is old and full of holes."

“Goodness! Then why did you bring it along?"

“I didn’t think it would rain."

__________________________

I love stories of fools and tricksters and foolish-wise sages/animals/elders and so on. And nowhere is there to be found a population as rich in fools as the legendary city of Chelm. I read several Chelm stories to Taliesen last night and had us both laughing and, of course, cancelling out any relaxing bedtime story effect. I found myself laughing at some familiar tales all over again as i listened to myself read them and also listened through Taliesen’s experience. I was delighted and amazed at how quickly Taliesen picked up on the cleverness of the humour. I know many an adult who would not be so quick.

Once again i was impressed with the way that wisdom can be encoded in stories of comic misunderstanding. And this story, in particular, struck me as carrying in it something important to understand better about our current moment of climate crisis. But i’ll leave off carrying that thought any further here and let the story work in the way that stories work.

image: Vyacheslav Beda

Saturday, February 16, 2019

What to Ask

Two monks met each morning in the garden to walk silently around the monastery. One morning, one of the monks said that it might be pleasant to smoke a cigarette as they walked. The other monk agreed but said, “let us first ask the abbot.” The next morning when the monk who had mentioned smoking arrived in the garden, he saw his fellow monk already waiting and smoking a cigarette. “But did we not agree first to ask the abbot about smoking?”

“We did agree and I did ask.”

“But when I asked, the abbot refused permission.”

“Ahh, what exactly did you ask?”

“When I approached the abbot I asked, ‘Master, when I am walking and meditating in the garden, is it permissible for me to smoke a cigarette?” To which the Master said, ‘Absolutely not!’ Just what did you ask?”

“I said, ‘Master, when I am smoking in the garden, is it permissible for me to meditate?’ To which he replied, ‘Certainly.’”

“We did agree and I did ask.”

“But when I asked, the abbot refused permission.”

“Ahh, what exactly did you ask?”

“When I approached the abbot I asked, ‘Master, when I am walking and meditating in the garden, is it permissible for me to smoke a cigarette?” To which the Master said, ‘Absolutely not!’ Just what did you ask?”

“I said, ‘Master, when I am smoking in the garden, is it permissible for me to meditate?’ To which he replied, ‘Certainly.’”

image:

pepe nero

Tuesday, February 12, 2019

Consensus and Consensus Decision-Making

I recently shared some thoughts on consensus and consensus decision-making with Toronto350. So i'm posting below some writing about consensus that i did with my colleagues at The Catalyst Centre (our website is offline for the moment - alas).

In reviewing my thoughts about consensus, i remembered this piece by David Graeber: Some Remarks on Consensus. So many excellent points. I agree with most of what Graeber writes though, he is, at times, a tad glib. I particularly appreciate that he addresses what "consensus" is as distinct from a process of decision-making. I think it very useful to distinguish between consensus as a set of principles (as Graeber describes it) and consensus decision-making which is, in my view, a codification of consensus as a decision-making process. And there are many examples of such codifications, one of which is posted below. Graeber very helpfully states that consensus "ultimately comes down to just two principles: everyone should have equal say (call this "equality"), and nobody should be compelled to do anything they really don't want to do (call this, "freedom.")"I agree with these principles though i use slightly different language: "everyone should have equal opportunity to have their say" (arguably this is implicit in Graeber's more succinct phrasing); and, consensus should be free of coercion. The principles of equal opportunity and non-coercion are anything but simple. Creating the conditions for equal opportunity requires great effort and a commitment of appropriate resources. Practicing non-coercion (or "freedom" as Graeber terms it) requires actively recognizing the numerous forms of coercion structured into society and culture - white supremacy and racism, class and capitalism, ableism, etc. etc. No easy thing. But essential.

It follows then, in my take on consensus, that learning/pedagogy is also an inseparable element of adhering to the principles of consensus as well as practicing whatever form of consensus decision-making a group may create and adopt. This means recognizing the need always for new members of a group to be able to learn the processes as well as an ongoing need on the part of everyone continuously to learn about the process in the context of group work and collective decision-making, and about power and resistance in society as a whole. I believe that it is for lack of practicing a robust commitment to critical learning that many attempts to function by consensus fail.

Finally, i believe that neither consensus decision-making nor any of many versions of "rules of order" are inherently democratic. Rather, what is democratic is what a group decides on and chooses to practice. All "rules of order" (including consensus decision-making) are vulnerable to being manipulated for the benefit of the few at the expense of many by someone who has greater knowledge and experience of this or that process (and a lack of scruples). All groups developing structures of decision-making, accountability, and so on should develop their own process (ideally building on past experience). And whatever process is adopted should always be open to criticism and change.

In order to encourage the ongoing learning i believe necessary, I list some resources at the end of this post.

It’s important to recognize a couple of common sense meanings of consensus. The first is one that circulates widely in the mass media and within public political culture. We often read about the “consensus” of the people, political consensus, the Washington consensus and even the “manufacture of consent”. Each of these uses refers to some form of widespread agreement about the way things are or ought to be. But this type of “agreement” results from the complex ways in which some voices and opinions are privileged while those of the majority are silenced or ignored (see the work of Noam Chomsky in Manufacturing Consent - the film or the book – and Antonio Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks).

FIVE WAYS TO DISSENT

SOME RESOURCES worth checking out

In reviewing my thoughts about consensus, i remembered this piece by David Graeber: Some Remarks on Consensus. So many excellent points. I agree with most of what Graeber writes though, he is, at times, a tad glib. I particularly appreciate that he addresses what "consensus" is as distinct from a process of decision-making. I think it very useful to distinguish between consensus as a set of principles (as Graeber describes it) and consensus decision-making which is, in my view, a codification of consensus as a decision-making process. And there are many examples of such codifications, one of which is posted below. Graeber very helpfully states that consensus "ultimately comes down to just two principles: everyone should have equal say (call this "equality"), and nobody should be compelled to do anything they really don't want to do (call this, "freedom.")"I agree with these principles though i use slightly different language: "everyone should have equal opportunity to have their say" (arguably this is implicit in Graeber's more succinct phrasing); and, consensus should be free of coercion. The principles of equal opportunity and non-coercion are anything but simple. Creating the conditions for equal opportunity requires great effort and a commitment of appropriate resources. Practicing non-coercion (or "freedom" as Graeber terms it) requires actively recognizing the numerous forms of coercion structured into society and culture - white supremacy and racism, class and capitalism, ableism, etc. etc. No easy thing. But essential.

It follows then, in my take on consensus, that learning/pedagogy is also an inseparable element of adhering to the principles of consensus as well as practicing whatever form of consensus decision-making a group may create and adopt. This means recognizing the need always for new members of a group to be able to learn the processes as well as an ongoing need on the part of everyone continuously to learn about the process in the context of group work and collective decision-making, and about power and resistance in society as a whole. I believe that it is for lack of practicing a robust commitment to critical learning that many attempts to function by consensus fail.

Finally, i believe that neither consensus decision-making nor any of many versions of "rules of order" are inherently democratic. Rather, what is democratic is what a group decides on and chooses to practice. All "rules of order" (including consensus decision-making) are vulnerable to being manipulated for the benefit of the few at the expense of many by someone who has greater knowledge and experience of this or that process (and a lack of scruples). All groups developing structures of decision-making, accountability, and so on should develop their own process (ideally building on past experience). And whatever process is adopted should always be open to criticism and change.

In order to encourage the ongoing learning i believe necessary, I list some resources at the end of this post.

CONSENSUS DECISION-MAKING

by The Catalyst Centre,

October 2006

Consensus

decision-making is a democratic and rigorous process that radically respects

individuals’ right to speak and demands a high degree of responsibility to

ensure mutual benefit.

Consensus,

like democracy, has many meanings. When we use consensus as a decision-making

process we must narrow this range.

And even as a decision-making process

there are many interpretations of what consensus means and how it can be

applied. What it comes down to is what a group agrees upon as a definition and

practice of consensus. Take a page from those who advocate for the use of

appropriate technology. Despite its lack of cogs and wheels consensus

decision-making is as much a technology as any tool or practice fashioned by

humans. And, as with all technologies, we should exercise caution and critical

mindedness in its use. To this end, it is worth drawing on the wealth of

experience with consensus around the world.

An

important part of what consensus is about is hidden in the history of the word

– its etymology. Taken apart, consensus becomes “com”, Latin for “with”

or “together”, and “sentire” meaning

feeling. So consensus means “to share the same feeling.” An interesting hidden

meaning in our hyper-rational world that all-too-often values reason at the

expense of emotion.

WHAT

CONSENSUS IS NOT

It’s important to recognize a couple of common sense meanings of consensus. The first is one that circulates widely in the mass media and within public political culture. We often read about the “consensus” of the people, political consensus, the Washington consensus and even the “manufacture of consent”. Each of these uses refers to some form of widespread agreement about the way things are or ought to be. But this type of “agreement” results from the complex ways in which some voices and opinions are privileged while those of the majority are silenced or ignored (see the work of Noam Chomsky in Manufacturing Consent - the film or the book – and Antonio Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks).

Another

unhelpful meaning of consensus is “no one disagrees strongly enough to speak

up” – i.e. silence is interpreted as consent. And, while this may be true after

a fashion, it is a dangerous interpretation of consensus if you wish to use

consensus decision-making democratically.

Consensus

is not unanimity. It is not 100% agreement on every aspect of a decision.

Consensus, to state the obvious, is not voting. Consensus is also not the

lowest common denominator that a group can agree on.

Consensus

decision-making does not need to be the only form of decision-making used by a

group. It’s up to the group to name and affirm appropriate forms of

decision-making for various things. Decisions can be made by voting,

compromise, bargaining, committees, facilitators, leaders, volunteers and by

self-selection.

SO WHAT

IS CONSENSUS ALL ABOUT?

Power!

It’s all about power.

As

usual.

Whether

we use consensus or voting, cooperation or competition, whether we rely on

executive decisions or go-with-the-flow, whether we acquiesce or collude,

passively or actively resist, you name it— it’s about power. About how we share

it, use it, abuse it, are oppressed by it, resist it or create more just uses

of it. Being in relationship with humans and human societies is about power. We

ignore this at our peril.

Democracy

through voting creates minorities who will always have at least three choices:

support the will of the majority (by deferring, submitting, etc.); withdraw

from the group (mentally, emotionally and/or physically); and work against the

majority (either openly or in secret).

Consensus

decision-making is a different democratic use of power – one that resists

creating minorities that lose. Different from democratic voting (commonly based

on one-person-one-vote) consensus is not necessarily better. This depends on

the circumstances and the type of decisions that are required. Consensus is as

open to being abused as any other practice. Consensus decision-making is an

appropriate technology for certain situations.

While

the goal in voting is to win majority support (usually defined as “simple”,

meaning 50%+1, or, for some things, “two-thirds”) for a position, the goal in

consensus decision-making is to develop a position for which there is a maximum

amount of agreement from all participants. When it comes down to voting for a

position participants have only three choices: in favour, against and abstain.

It can be very difficult to gauge the will of the group when voting is used.

Consensus, however, has many choices.

While

there are six identifiable choices in consensus decision-making (we can give

support, lukewarm support, support with reservations, we can stand aside,

block, withdraw from the group) in truth it is more like a continuum along

which people can find numerous places to stand. The plain wording of the six

choices is important in promoting clear communication that works well with

limited amounts of time. And the six clear choices make it easier when calling

for consensus to quickly determine the will of the group.

It

is worth noting that the first four choices in consensus decision-making could

all be expressed in a voting process as a “YES” (although some might use

abstention to express an opinion). You could say that consensus decision-making

has four ways to say “yes” and two ways to say “no.”

FOUR “YESes”

AND TWO “NOs”

There

are six identifiable options in consensus decision-making:

OPTION

|

FOR

EXAMPLE

|

1. SUPPORT

|

“I support the proposal as stated.”

|

2. LUKEWARM

SUPPORT

|

"I’m lukewarm. I don't see the need for

this, but I'll go along."

|

3. SUPPORT

WITH RESERVATIONS

|

“I think this may be a mistake but I can live

with it.”

|

4. STANDING

ASIDE

|

"I personally can't do this, but I won't

stop others from doing it.”

|

5. BLOCKING

|

"I cannot support this or allow the group to

support this. It is immoral."

If

a final decision violates someone's fundamental moral values they are

obligated to block consensus

|

6. WITHDRAWING

FROM THE GROUP

|

“I feel that this group does not and will not

represent my interests. I

believe it is best if I leave the group at this point.”

|

FIVE WAYS TO DISSENT

Consensus

decision-making values dissent – it welcomes it, recognizing its creative

force. You could say that consensus decision-making has five ways to dissent.

Dissent

requires a willingness to argue, disagree, even getting passionate. If a group

is committed to developing a proposal for which there is the maximum shared

feeling, it is hard to imagine that this could happen without some good and

passionate arguing. Conflict can be creative, provocative, challenging. It can

help participants in a debate test their own clarity of thought and emotion; it

can help reveal the depth of commitment to an idea, a position, a feeling.

Many

people think that strong emotions prevent consensus. This is because strong

emotions are often equated with aggression or violence and, while they can be

used to silence and intimidate, they can also be used with respect. It is

especially important to recognize different cultural (including gender, race,

class, age, etc.) choices and values regarding expressing emotion. Some

cultures value reserving expressing strong emotions only in private places

while maintaining a calm and rational demeanor in public. Some cultures expect

strong emotion to be expressed publicly as a demonstration of commitment while

still others see this as a loss of control.

Strong

emotion is often linked to violence and coercion. And this should be

acknowledged. For example, it is a commonplace for North American men to raise

their voice as a means of intimidation. It is also common for some people to

drop their voice to force people to ask them to repeat. Both of these are

examples of manipulation that is unhelpful (even damaging) to a consensus

process.

What

is important for consensus decision-making is to be conscious and

critically-minded about the many ways emotion is legitimately expressed and for

the group (at some point) to negotiate some forms that are acceptable without

unduly silencing any of its members. It can be a huge mistake simply to accept

and affirm that the only form of debate and communication is cool, calm,

collected, never-raise-your-voice, rational speech.

ENSURING

HIGHEST QUALITY DECISIONS

People

are more likely to carry out and/or defend a decision that they accept. What

obliges a person who lost a vote to implement or defend that decision?

One

of the great strengths of consensus decision-making compared to voting is the

amount of information shared about the quality of the decision. A “yes” vote

does not communicate much about what a person might mean by that “yes”. Perhaps

they are heartily enthusiastic or perhaps they are simply so fed up with the

debate that they just want it to be over with. Both positions are equally

well-represented by a simple “yes” vote. Consensus recognizes both of these

positions as supporting the proposal but also gives people a few choices with

which to represent their position: from fully supporting to being lukewarm to

expressing cautions or provisos to standing aside to allow the group to go

forward because one doesn’t feel strongly enough to stop the group from going

ahead.

The

information about the quality of people’s support can be very helpful to a

group in making effective decisions. How often have we seen groups decide to do

something only later to complain that, despite a majority “yes” vote, no one

showed up to carry out the decision. Using consensus decision-making a group

might have seen that only two or three people were fully supportive while many

were lukewarm and many stood aside. Seeing this, someone could have advocated

for revisiting the proposal and changing it to win stronger support. Or the

group could still stand by its decision – which tells the few who were strongly

supportive the likelihood of their compatriots showing up to follow through.

For some decisions a group might consider it acceptable to support an

enthusiastic minority while with others the group might deem it essential to

have majority enthusiastic support.

Sometimes

the position of a single person (or a critical few) is crucial. Consensus

allows a group to gauge the quality of that single person’s support. If that

person is supportive with

reservations or chooses to stand aside, the decision might not be

workable. The group could continue to work on the proposal to make a decision

for which that person would be more enthusiastic.

TESTING

FOR CONSENSUS AND STRAW POLLS

The

process of testing for consensus often stumps people and groups that are used to voting (by

asking for a show of hands, saying “yes” or “no”). One advantage to “testing”

is that once a consensus is reached the group can evaluate the quality of the

consensus. If too many people are lukewarm, even though consensus has been

reached, some people might wish to change their position or move to re-visit

the decision.

Short

of testing for consensus, the group could decide to call a straw poll. This is

usually done by asking for a show of hands of those who support the proposal so

far. A straw poll is a non-binding opinion check. This is often mistaken for

voting – it is NOT voting and should not be allowed to be used in this way. It

is easy to slide from a straw poll into a hasty reading of consensus. This can

easily silence many people. An individual who indicates support for a proposal

in this way is not committing themselves at this point in the debate. A straw

poll should only be used if there is time to respond to the results. If there

are five minutes left in a meeting it is probably unwise to use a straw poll.

In this event it would probably be better to test for consensus or table the

decision to a later date.

BLOCKING

AND HOLDING A GROUP HOSTAGE

Blocking

is one of the strengths of consensus and, like any strength, it can also be a

weakness. Blocking is an extreme choice and should never be used lightly.

Anyone or any party considering blocking has the responsibility to ensure that

all other options have been exhausted and that they are not acting out of

self-interest, bias, vengeance, fear, etc.

Many

people unfamiliar with consensus fear that blocking will lead to impasse. And,

in truth, if a group is inexperienced with consensus, this is a possibility. It

is the responsibility of both the group and the individual to sustain an

understanding of the many choices available in a consensus decision-making

process as well as to promote the critical awareness that consensus is about

rights and responsibilities.

If

a decision (that has been fully discussed and is ready for testing) violates

someone’s moral principles or if they feel that a decision violates an

agreed-upon principle of the organization then they have an obligation to

block. If this implies that deciding to block is close to deciding to stay in

or leave a group this is often the case. If someone is choosing to block it is

because “standing aside” is not satisfactory and a group is about to make a

decision that crosses a line. If a group fails to respect the right for someone

to exercise blocking then this is a

point that someone might want to consider the final option of consensus

decision-making: withdrawing from the group.

NOTHING

IS ABSOLUTE

If

a group feels that one person or party should not have the power to block a

decision it is possible only to allow blocking by two people or parties. One

person blocking would not enough to stop consensus. Some groups call this

“consensus minus one”. Depending on the size of the group it is conceivable

only to allow blocking by three people. This should be done very cautiously.

Should a group increase the limitation on blocking thoughtlessly you could end

up with a situation in which it requires 25% of the participants to block which

might become a defacto voting process.

It

is also important to consider group size. Consensus decision-making can take

more time than majority vote processes. For each participant of a large group

to have the opportunity to speak can take more time than a group has. Groups

should consider using small group discussions (from pairs to groups of five) to

facilitate decisions.

A

group should also be critical and creative about how voices get represented in

a discussion. In coalitions it is common for each organizational member to have

one voice regardless of the number of members of that group present (each

individual can still be granted full rights to speak while limiting each

organization to one voice when testing for consensus). Unaffiliated individuals

in a coalition effort can be asked to form affinity groups for the same

purpose. These are processes for democratically balancing mutual interest with

individuals’ interests.

It

is also important to always consider the needs of newcomers. Consensus

decision-making requires a constant process of education and critical

reflection. Newcomers should receive an orientation to the process and should

be expected to agree to the responsibilities of consensus if they wish to enjoy

its rights. A group might oblige newcomers to attend one or two meetings before

being granted the right to exercise a voice in consensus decision-making.

Groups

using consensus decision-making should be vigilant about resisting groupthink

which is always a risk when silence is assumed to mean consensus. If time has

been used poorly, if an issue has dragged on too long, if a few vocal people

have dominated, many group members may simply submit rather than continue to

resolve differences.

FIVE

GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF COALITION PARTICIPATION:

Coalitions

of groups require articulating shared principles in order to work

democratically and effectively. Coalitions often use some form of consensus

since groups whose interests are not being served always have the option to

leave. The following five principles are adapted from Filipino coalition

experiences:

1. Democratic Pluralism: the coalition will

include many democratic forces with different but some overlapping goals. We

acknowledge that we don't all know each other.

2. Consensus: the coalition will work

by consensus and use a formal process of consensus decision-making. We agree to

work by persuasion not coercion.

3. Independence and

initiative:

coalition members unite on common issues while remaining free to pursue other

activities outside the coalition according to their missions (as long as these

don't violate principles and objectives of network unity). Unaffiliated

individuals who are members of the coalition are encouraged to seek affiliation

through a member group or otherwise self-organize with others (individuals can

form a new group that could formally join the coalition or use an affinity

group process to represent like-minded allies).

4. Shared

responsibility: each coalition member must share in coalition work on a basis of

ability according to size and resources and not on a basis of reward. We are

all responsible for creating and maintaining a culture of participation.

5. Unity and struggle: no member of the

coalition can advance at the expense of others. Although programs and lines may vary, coalition members

should welcome and encourage dialogue on matters related to realizing higher

levels of political unity and understanding. We agree to open sharing of

information amongst members and we encourage healthy and democratic debate and

discussion.

AT A

GLANCE GUIDELINES FOR CONSENSUS

·

Consensus requires a good degree of trust within a group.

·

Consensus decision-making requires effective facilitation. The

facilitator is responsible for ensuring that everyone’s rights to participate

are respected and that everyone is encouraged to act from a position of

responsibility. The facilitator is always responsible for ensuring (through

recommending and/or negotiating changes) that the process is serving the

interests of the group.

·

It is both a right and a responsibility of each participant to challenge

the process if it is not serving the interests of the group.

·

Not all decisions require consensus. Be critically-minded about how and

when to use formal consensus.

·

Any participant can suggest that consensus be tested. (i.e. the

facilitator then has the option to allow debate to continue; to test consensus

using a straw poll; to test consensus by asking people to state their

position.)

·

A straw poll is not a vote and should not be used, even informally, as a

voting process. If a straw poll is called (and agreed to) it is a means of

providing information to the process of dialogue. The results of the straw poll

should be addressed and those who did not express an opinion should be asked

for more information. Even if the straw poll reveals unanimity, this should not

stop debate. The group should be asked if they are ready to test for consensus

and, if ready, then consensus should be tested.

·

Once debate on an issue is complete the facilitator (or chairperson)

will test or call for consensus (e.g. “Can I ask everyone to state their

position on the proposal?” It is always advisable when groups first start using

this process to ask people to state their position verbally.)

·

Participants in a formal process of consensus decision-making have four

different ways to say yes, two ways to say no or, to put it differently, five

ways to dissent.

·

N.B.: Obviously, if many people declare themselves as “lukewarm” or “stand

aside” or “leave” the group, it

may not be a viable decision even if no one directly blocks it. In such

cases, it is wise to revisit the decision given that it might well be

un-implementable. It could be worth reversing the decision, nullifying it, or

tabling it for future re-consideration.

Emergent Strategy by Adrienne Maree Brown (2017, AK Press) is what I am reading currently. Part memoir, part theory about resistance to oppression, part handbook about better group process, and more - this book is well-worth the effort. I first learned of Adrienne Maree Brown on account of her work on Octavia's Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Movements, a work honouring the work of the late Octavia Butler, one of my favourite and most beloved authors (I await, with excitement and anticipation, the opportunity to see the opera by Toshi Reagon based on Butler's Parable of the Sower.) Brown's book includes two chapters of practical "tools": spells and practices for emergent strategy and tools for emergent strategy facilitation, both of which are excellent sources of processes for creative and critical resistance work.

The Empowerment Manual: A Guide for Collaborative Groups by Starhawk (2011, New Society Publishers). I've been a big fan and follower of Starhawk since first encountering her work in the 80s. I've read all her books and loved each and every one (not simply because i'm a nerdy completist). Her book Truth or Dare is simply packed with good theory and good practice. The Empowerment Manual unlike many process books (Emergent Strategy being another rare exception) is an excellent read - i.e. both content and form make it a good read. Starhawk embeds her process theory and practice (or dare I say, praxis) in scenarios that read as small dramas in which it is possible to imagine oneself participating. I have used Starhawk's work in my popular education work for many years and this book is excellent pedagogy!

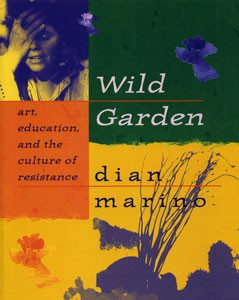

Wild Garden: art, education and the culture of resistance by dian marino (1998, Between the Lines). dian was a beloved friend and has been much missed since her death in 1993. Following her loss some mutual friends and I worked on dian's papers and transcripts of talks to edit this book of theory and practice. It includes some excellent popular education and art methods for critical, creative, and insurgent creative learning and teaching. dian's work can be a very good primer to reading Antonio Gramsci's work, something i encourage you to do. dian's praxis is also, refreshingly, playful!

Jugar y Jugarse: Las técnicas y la dimensión lúdica de la educación popular by Mariano Algava (2006, Ediciones América Latina) PDF. I loved this book the minute i learned of it and it remains available, after many years, for free download as a PDF. An inadequate translation of the title is "Play and Playfulness: The techniques and playful dimension of popular education." But here, the term jugarse/playfulness has the sense of "playing with abandon" - i.e. the risky nature of play. The book is unapologetically committed to radical social transformation, even revolution. I wrote a longer intro to this book here which also includes a few paragraphs translated from the introduction. I find a huge lack of discourse/theorizing in social movement theory and practice about the nature of play and playfulness. Humour does show up in demonstrations - from clever placards to giant puppets (i have been privileged to carry Bread and Puppet puppets in a demonstration). But perhaps we eschew theorizing about play and playfulness for fear of spoiling the fun - ruining the joke, as it were. And yet, laughter is both rebellious and revolutionary. And it's good for the spirit. But more importantly, perhaps, this book looks at how play and playfulness is a necessary part of learning which is part of the "emergent" (apropos of Brown's book mentioned above) process of becoming new subjects/actors of a history of the future that has in it more love and compassion for each other and our tortured planet.

The Empowerment Manual: A Guide for Collaborative Groups by Starhawk (2011, New Society Publishers). I've been a big fan and follower of Starhawk since first encountering her work in the 80s. I've read all her books and loved each and every one (not simply because i'm a nerdy completist). Her book Truth or Dare is simply packed with good theory and good practice. The Empowerment Manual unlike many process books (Emergent Strategy being another rare exception) is an excellent read - i.e. both content and form make it a good read. Starhawk embeds her process theory and practice (or dare I say, praxis) in scenarios that read as small dramas in which it is possible to imagine oneself participating. I have used Starhawk's work in my popular education work for many years and this book is excellent pedagogy!

Wild Garden: art, education and the culture of resistance by dian marino (1998, Between the Lines). dian was a beloved friend and has been much missed since her death in 1993. Following her loss some mutual friends and I worked on dian's papers and transcripts of talks to edit this book of theory and practice. It includes some excellent popular education and art methods for critical, creative, and insurgent creative learning and teaching. dian's work can be a very good primer to reading Antonio Gramsci's work, something i encourage you to do. dian's praxis is also, refreshingly, playful!

Jugar y Jugarse: Las técnicas y la dimensión lúdica de la educación popular by Mariano Algava (2006, Ediciones América Latina) PDF. I loved this book the minute i learned of it and it remains available, after many years, for free download as a PDF. An inadequate translation of the title is "Play and Playfulness: The techniques and playful dimension of popular education." But here, the term jugarse/playfulness has the sense of "playing with abandon" - i.e. the risky nature of play. The book is unapologetically committed to radical social transformation, even revolution. I wrote a longer intro to this book here which also includes a few paragraphs translated from the introduction. I find a huge lack of discourse/theorizing in social movement theory and practice about the nature of play and playfulness. Humour does show up in demonstrations - from clever placards to giant puppets (i have been privileged to carry Bread and Puppet puppets in a demonstration). But perhaps we eschew theorizing about play and playfulness for fear of spoiling the fun - ruining the joke, as it were. And yet, laughter is both rebellious and revolutionary. And it's good for the spirit. But more importantly, perhaps, this book looks at how play and playfulness is a necessary part of learning which is part of the "emergent" (apropos of Brown's book mentioned above) process of becoming new subjects/actors of a history of the future that has in it more love and compassion for each other and our tortured planet.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)